Gunfire and Flan: Creating Community in a Drug War Zone

When the War Came to My Favela

My first week at Morro do Providencia, the oldest favela in Rio, was met with hand grenades exploding 1/4 of a mile away from where I was eating. The grenade stopped an armored vehicle, painted with a skull and crossbones on the side. I ducked at the sound of Kalishnikov Rifles firing from the narrow alleyways up the hill.

I am a Community Artist. Which means I am an artist who uses story and storygathering techniques inside of communities to build stronger relationships. I live in these communities during the time I am working on their project, which is usually between 12 and 18 months, so it gives me a real immersion experience. It helps me understand diverse cultures on a profound basis. It also means I am constantly honing my own craft, as well as my lifelong education about what I can do, myself, inside of my own community.

But can you build community and relationships everywhere? Especially in a place that has become a war zone? In a place that, perhaps, needs community more than anywhere else?

My time in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, solidified my commitment to this work, when I experienced, first hand, what will and does happen when relationships are broken, prejudice takes precedence, when the voice of the people is extinguished, when the story of who they are and what they can be, where they come from, is lost or rewritten. Living there was a frightening experience at times, but what was worse than the fear for my own safety was the recognition that, perhaps, some things can be broken so badly, relationships so damaged, that working for change is futile. By the end of my journey, I would find the answer to my question: "What difference in the history of the world will my being here make?"

I struggled with this question so much, that I kept a nearly daily journal, and photographed my project extensively during the last months of the project. This lens contains those journals and photos. I also include the journals and photos of my partner in this business, Dr. Richard Geer.

Spots of Light

April 11

We're here in Rio working on a new project. Sure, every project has its difficulties before getting started, but here is a new one. Thought you might appreciate it.

So, some places, we've not had lights installed, and that was a nightmare. Other places, the seats were not yet in place on opening night, and they were hammering them in at 4:00 that very day. We've had our leading opera singer stung by a wasp the day before opening and she had a reaction, ballooned up and started going into shock. We had both of our lead actors in Chicago disappear on us, on the very night we had visitors from around the country come to the performance, and instead, saw Al read off of a script. Small stuff. This is what happened to mark the beginning of the Instituto do Methodista production two weeks ago.

Three military trucks, filled with heavily armed soldiers drove through the tunnel, came into the Institute (NOT the favela, but here) and began firing everywhere. The helicopter above started shooting the rooftops of the Institute - NOT just the favela. Tore the devil out of the Instituto's new Pavilion roof - for what? Target practice? Meanwhile, soldiers begin making their way up the hill to the favela. Everyone scrambles for shelter. Our composer/local director, Ronaldo, gets stuck behind a locked gate, trying to get the lock and chain open, so he can get to the 2nd floor. (the locked gate is usually for our protection so no one can come in to our area, but now he can't get out of it to try to save his life.) The helicopter is shooting, there are RPGs tearing through rooftops and concrete walls. You do not want to be on the third floor right now (top floor). The middle of the building is safest. Twenty rounds go into the side cresche (nursery). Children are inside. More than a hundred bullets tear through the pavilion. A worker at the Institute, painting a wall when this happened, had a bullet hit the wall in front of him and it shattered and damaged his face.

The Commando Vermehllo (the drug traffickers who run our favela) are shooting back. The CV are on the hill, up and hidden away in the favela, and I don't know why, but the military is shooting up our Institute, which sits at the bottom of the hill. They don't care that innocent people - children and babies too, are inside. There was no warning here before the machine guns started blazing. Affter an hour or so, the institute Director arranged a 30 minute cease-fire to move the babies out of they nursery. Then it begins again. More troops come. Streets are blocked off. The news comes again (this favela gets the most press and the most military and police action). It is war. Pure and simple war.

A two year old and a twelve year old boy were killed on the hill. No one is supposed to talk about it.

Inside the pavilion, you stand on the floor now and it looks like a mirror ball is hanging inside - spots of light are pouring through the holes left by the huge rounds that tore through the roof, and the dots of light dance on the floor. Bullets are embedded several inches into the concrete walls and seats.

This is where we will perform. The damage is devastating, and I think of what must have happened to those two children, how mangled they must have been. But no one can talk about it.

I must go, more later. Have to go to work, they're calling me. Just to let you know- everyone at the Institute was safe. Only the one injury of the worker. And Ronaldo did get that lock open and make it to the second floor. OK, more later.

- - - - - -

OK, back now, so more of the story. The army comes back and this continues for three days. There was supposed to be a special program planned for Saturday, the food was already prepared and everything, but it had to be canceled because of the fighting. No one would come anyway, because it was all in the papers. Some people from the Instituto who have other places to go, leave - it's too dangerous. What is left afterward is a huge mess to clean up.

Scaffolding is up around the buildings now, and people from around here come to help make repairs. They pull off the broken stucco and start putting up new stucco, and plaster in the holes in the wall. Hard, hot work, especially when the scaffolding is not that secure, the floors are easily 35 feet high, they use a rope to sort of hold the scaffolding to the building, so as the workers climb it, it doesn't lose balance and tip over. Third world construction. Richard took some pictures- it is unbelievable. Creative problem solving at it's scariest and best.

Marion, the Institute Director, called the army office and complained about the roof of the pavilion and all the damage. This is a very poor Institute. When they got the new pavilion roof just a couple of years ago, it was a VERY big event - that they were able to afford it. This provides a place for the people to play ball, to hold events, it is used every single day. Today, a capoeira group is practicing there. And now, the roof is destroyed. Rain and rust will do it in if it isn't repaired. The army has not answered yet. Marion said if they do not make things happen for repairs, then they will protest. Not that it would matter. It's the lack of value for the human beings that live here. Just like the children who were killed. To them, it's just a couple of more kids who won't be on the streets. But the majority of our project's participants are kids. That's the reason closest to my heart, why I came to work here. I'm not quite sure exactly what it is we will finally be able to do. I don't know. I guess as this project unfolds, we'll find out.

Repairs Being Made after the Siege

Some Background on the Project

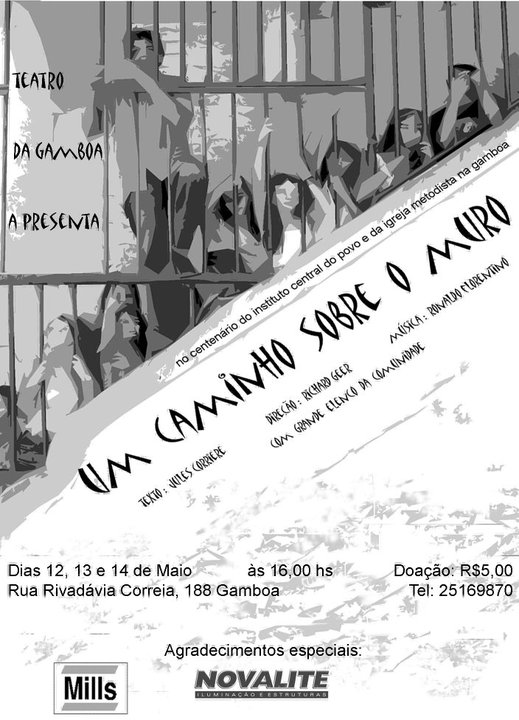

A group from a Methodist Institute from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, saw a community-building production of mine called "Swamp Gravy" when they were in America. They were impressed with the project and its possibilities. They then brought in a Swamp Gravy Institute contingent, including community builders and organizers, as well as community actors and storytellers. The Swamp Gravy people performed, and then, with the help of others from the Instituto in Brazil, did some story gathering, and created small performances at the church with the people in Rio. It was decided by the leaders at the Instituto that this would be a good program for them, especially to mark their 100th anniversary of their mission work, which serves the people in the favela above them. They then invited ,y business partner, Dr. Richard Owen geer, to come on a primary visit and get them started. Last year, the two of us came here together to collect stories, to create more interest and participation, and to begin forming the project with local leaders. Now we are here actually in the process of doing the Theatrical Community-building project.

About the war here.

The favelas are claimed by one of three main drug cartels. This has happened because the city of Rio historically has not recognized the favelas or the people living in them, even though 1/3 of the population of Rio lives in these ghettoes that rise up the hillsides throughout the city. Municipal water, electricity, and services often do not reach these places. They are a "no-man's land" (no-person's land) and go to the group with the biggest arsenal. The drug trade happens within these favelas.

We are at the bottom of one of Rio's more notorious favelas. The drug lords are heavily armed. I've seen some of the teenagers, when I went up there, with hand grenades hooked to their belts. They are the local law enforcement, and often take better care of the residents than the police.

The cartels are at war with the city and the government police. I don't really know how to use those terms either, because often, the people who are involved in the drug trade in one favela serve as police officers in another. I have heard just as many stories of horror done by police as by the drug lords. I tread softly around all of them. Very softly.

This past year, it has appeared to locals that the police favor one drug cartel over the others, and have begun invasions into favelas run by the other two cartels. We are in one of those which was stormed by the military a few weeks ago. Our Favella is run by Commando Vermehllo.

Within all of this turmoil, the Institute wants to celebrate the fact that through these very difficult 100 years, they have been committed to the work of service, and that as long as there is need, they will be there to serve the people, even when the city closes its eyes to the human beings living here.

The Smell

Jules Corriere, April 12

The smell, the smell, everywhere I go it follows me here. Walking to the Cemetery, there is running water on the very narrow side of the street where I walk, coming from people washing cars on the curb mixed with raw sewage coming down the hill, and exhaust from the busses turning dangerously fast past the corner. I keep thinking-"You are a snob, Jules!" I am, I don't like the smell, I don't, and what a little thing it is-where so much else is going on: Bullet holes the size of fifty-cent pieces embedded six inches deep into the walls of the Instituto where I live, new holes appearing on a nearly weekly basis. Children being shot in the streets because there is a problem with too many children without homes here, and that is the military's solution. Hunger at the doorsteps of those lucky enough to have doors, and I see that, all of that, and I feel it, but it does not affect me the way this smell does. It makes me sick, and fatigued. Perhaps, because I can close my eyes, and stop looking at the hard things here, but I cannot stop breathing. Perhaps that is what it is - the scent of life trying to happen, and it is this struggle I am breathing in, and it goes through me with every breath I take-inescapably. I must keep breathing in the struggle. The smell reminds me of the things I wish I did not have to see, and wish I did not know, but exist whether I look at them or not.

The Asfalto

Richard Geer, April 13

I thought that everyone would be from the favela, not true. The majority are from what the moradores, the favelitos, call the asfalto. It means, literally, "asphalt," but it contrasts. In the city proper, the streets are paved, not so in the favela. Cosme (CAWS may), a boy from Morro do ***, the favela behind the institute, is an extraordinary talent. He is over six feet tall, still with the narrow shoulders of a child, but with old eyes. He is my strongest memory from the rehearsal last night.

He was the drunk husband. "The drunk" not "a drunk" the specificity was amazing. He rocked onstage as if his feet were rounded on the bottoms. The same with shoulders and lolling head, all rolling. He was, at a glance, the-impoverished-husband-father -to-too-many-children-to-feed-so- let's-have-a-drink-what-the-hell.

Two things were immediately obvious, Cosme has a huge talent and he knows domestic violence. He is one of these actors who makes it look as easy as a cat curling into sleep. Perhaps his relaxation draws us into his reality. He is unflappable, unbreakable, the actor with him, twice as old, keeps breaking into laughter. It is laughter as pressure release, Cosme's reality is like thrown punches. She expected the pulled blows of "acting." But he isn't pulling his emotional punches, and she is on the ropes. When the scene is finished, with Ronaldo translating, I try to tell her that giggling happens at the fork in road, one fork leads back out to the silly world of pretend, rehearsal, and non-commitment. The other way leads into the story, into the trouble, into the heart of the character's predicament.

We're telling Eliete's story. Eliete (el ee AH chay) is the cook for the small kitchen that feeds some of the institute staff. There is a larger kitchen that feeds the children and the staff that takes care of them, but I don't know those folks. Eliete's story is featured in the play.

She was the abused wife of the alcoholic that Cosme played, and the mother of seven. She broke away from this relationship many years ago and came "down the hill" to the Institute. She came looking for Senor Mario, the boss of the Institute. The first person she ran into was a man sweeping. In a rather curt way, probably because she was nervous, she asked to be shown to the director. "I am the director," said Mario. She didn't believe him, nothing in the man's manner spoke of power or leadership. He was very quiet and unassuming. Eliete thought he was teasing her and stiffened, demanding to see the director. And when he again said that he was she was very embarrassed. She asked him why he, the director, was sweeping. Some visitors were coming, he told her. She told him, "Well, you go put on a tie, I'll sweep." And she has been working here ever since.

After rehearsal last night I ate one of her meals, a simple working person's stew of potatoes, beef, sausage and vegetables over rice. And of course the ubiquitous rice and beans which are de rigueur at every meal except breakfast and are delicious with hot sauce and a sprinkling of yucca flour prepared with spices, called farinha (fa REEN yuh).

The Great Pig

April 14

We're going to have to get a lot more organized. This is Easter weekend, it's kind of a loss. But it's the time in which we'll finish the play and get our ducks in a row. Brazilian Time is very slow. We don't even go down to rehearsal at the nominal time of the beginning. That is more like when someone might think about leaving home. So if you lived a half hour away, when you saw that it was 6PM you might get up and begin to get ready, and maybe roll out of the house by fifteen after and take half an hour to get there and walk in at 6:45. Six is the starting line, not the finish.

I'm not going to tackle that monster at present. I'll just adjust the nominal beginning time for a workable arrival time. This timing created a typical result. We were to meet at five in the afternoon to take a publicity photo. It is nearly a month into fall down here, so the days are shorter all the time. There is light at five, but not for long. In the afternoon word came that Mario would take us up to the wall on the hillside at 5:15. But by that time, he was not there and the light seemed pretty much gone anyway.

Okay. So I scouted the place up the hill for the photograph. The Institute clings to the side of a hill. The drive in is steep but there is a nice semi-leveled place that is parking and courtyard soccer. The main buildings are on either side. The hill goes straight up on the west and south of the property. For decades the favela has been throwing garbage over the wall onto the steep hillside that is the beginning of the Institute property. Today it is little more than a landfill lorded over by the great pig and his (or her?) harem of smaller pigs.

The great pig, it is said, is the property of dono the head of o trafico, literally "the traffic" in the favela. Nobody harms this pig. And it is toward him that I am climbing with a camera to check the light for a possible shoot the next day. Edmundo (edge-ay-MOON-doe) goes with me, a familiar face, so I won't be mistaken and shot, I guess. I climb up through the garbage about halfway to the wall and see that it will not be lit by the setting sun, so scratch that plan. I take a few pictures of the garbage and the pigs, and a boy picking his way home through both.

Light is fading fast but we are waiting for xeroxes of the scene of Helga and Dr. Tucker. Helga was a choir teacher from Germany who was notorious at the Institute. She was very strict, but she spoke funny Portuguese, so being in her class was serious and laughable. We're dealing with two groups of kids in the scene. Smaller ones are the flute class (they pretended to play the ditty all of us know: "there's a place in France where the women wear no pants...").

Bigger ones are in Helga's choir. The kids are patient and pretty focused. Not the cutting up that we normally encounter. And kids have time here. We are a real diversion for them and they seem eager to play with us. In the states we have to battle for a kid's attention against the streets or soccer or dance classes. Doesn't seem to be a problem here. The children are all neat and clean. They manage clean clothes, sweet smells and nicely cut hair, thereby sanitizing and erasing the most obvious markers of poverty. They come from families, that's clear, and they have a home where hygiene is valued and, more importantly, possible.

A Bicycle

April 15

We have about twenty people who want to come all the time, children. They are probably going to be the core of the cast and adults will come, but not with such regularity or avidity. Jules, inspired now because she is here, and able--because finally we have heard some of the hard stories of the history--to write, is translating into words both stories and place. I don't know what I'm doing. We talked to Ronaldo about the importance of him being the director. We can't take the time to translate back and forth during rehearsal. And maybe some kind of a system started to work last night with Edmundo translating for me while Ronaldo worked the cast. I'm guessing my role will be to devise staging and then collaborate with Ronaldo to plan what will be done in rehearsal. But he will need to do it, because of the time-wasting translation thing.

Last night we did an exercise with the kids as we bide our time finishing the script. I asked them, through a translator, to tell me about the time in their lives when they were the most joyful. I'd seen previous improvs many times on this visit and on others. They are almost always violent. So I wanted to see their occasions of joy. It was a little game that begins with one person telling a partner a short account of a moment of joy. Then the listening partner tells it back in the first person, as if it happened to the listener instead of the teller.

This is always a strong experience, to hear your voice coming back to you, to be the subject of a story on someone else's lips. It is nourishing. Anyway, then the listener tells his/her own story and the original teller tells that back. Then they decide which one of the two stories they want to tell to another pair of people. If, for example, your story were chosen, then I, as your partner, would tell it to the next pair. In fours, these two stories are exchanged and then the four people (sometimes six) put the story on its feet.

In the group of kids from eight to eighteen, we got three stories. One about a birthday, two about Christmas. One of the Christmas stories was told by a raven-eyed girl with jet black hair, she looked almost like an Indian from the Subcontinent.

This little girl lives in the favela. Her hair dances down her back and it is so rich, heavy and full that I almost can't stop myself just from reaching out to heft it. She asked her parents for a bike for Christmas. Her father was broken-hearted to tell her that he couldn't afford a bike. So she turned to her mother. Of course, I can't understand their words, so I'm telling you only what I saw. Her mother didn't speak at all, just sat there. Finally she rose and went to a chest and brought out pen and paper so the child could write and mail a letter to Santa Claus, I suppose. Even the stamp was a challenge, you could feel the mother's hesitation to give it up. The next scene found the family, sleeping, awakened by a knock. "It's for you," the mother called from the door. Debra (the little girl) ran to the mailman who presented her with a big box (played by a bicycle thin girl of about twelve). As she was unwrapped the bike crouched down on hands and knees ready for its rider. The delighted child hopped on and pumped her legs on pretend pedals and steered the bike around the room.

These kids are expert on things close to their lives. Expertly simple, direct. Violence doesn't evoke surpise, comments or questions. It is. It stuck in my heart that remembered joy was in each case connected to days which were themselves already special. Birthdays and holidays are fun, but they aren't where I would look in my own life for joy.

I know how Mario gets the kids back. He gives treats. There is a Cheetos-like puffed snack made from Manioc. When I heard that Mario had scored it for the kids I laughed. It's called "Crac." I could see the headlines now...

Jules knew me well and saw to it that I got a huge salad with ranch dressing for my birthday lunch. The water in Rio is prone to bugs. Locals can drink it but visitors are advised not to. The water supply is okay, it is the leaky old pipes that get contaminated. Lettuce has to be grown and washed, and the bugs hang around, so we are advised not to eat lettuce. Jules found some hydroponically grown lettuce that Mario recommended, and some ranch dressing, tomatoes, cucumbers, radishes. It was a feast.

We spent the afternoon re-interviewing the Ways, Mario and Anita. More about that tomorrow.

Happy Easter

Jules Corriere, April 16

Feliz Pasquao! Happy Easter. It is a different holiday here than it is in the United States. It has not lost its reverence and its ritual. I wouldn’t expect to see Easter baskets and jelly beans here, first of all because no one can afford them, but secondly, it is not a holiday for marketing. This is still a very religious holiday, and since the most of Brazil is Catholic, the icons and rites and rituals are carried out everywhere. They don’t sell this holiday, they practice it.

On Friday, (Good Friday) all of the schools were closed. Some of them were closed on Thursday. The Instituto here has school for children, and their last day was Thursday. There was a celebration in the classes, and cake was served to the kids. This is a bigger event than you may think. Cake, and sweets in general, are a luxury. Children here may expect to get sweets like this only a few times out of the year. Cakes require cooking, and cooking requires an oven. People in the favela have hot plates fueled by kerosene, things like that. But no oven, no room for ovens, no room for tables. The houses are a place to sleep out of the weather, and most people spend their days outside of the houses, unless working, like washing clothes in the sink.

The other people who live around here, the people who live on the asfalto, are also always outside. There may be a community oven, but it is so hot, it rarely will be used. It is miserable inside these buildings. I believe I may have described this before - people in the favela have houses - built and pieced together, but they have windows, and there is a certain security - crime within the favela itself is very low (except for the drug trade.) There are very few murders and rapes. The ***(drug cartel) is the local law, and their punishment is swift and severe. Consequently, crime is low because of this.

The people who live on the asfalto (buildings on city streets, with rent) live in closed up, boarded up buildings, no windows (out of need for survival and security). Five to six families will live in one, with one bathroom at the end of the building. (At least there is a bathroom.) The conditions are often worse, certainly worse than the favela, but the trade off is, that they are not under the control of the drug cartel, so they have more personal freedom. But the Cartel does not control crime in that area like they do on the hill, so the people on the asfalto have to protect themselves. (I guess you’ve figured out by now that calling the police for help is a joke.)

Everyone is outside for this weekend. None of them have ovens or use ovens for preparing treats, save for these special occasions. So cake at the Instituto on Thursday was a huge event. I was given a piece of cake to take with me after leaving the classroom. Two of the younger kids I work with, Thalita and Talia, came to say “bon jea”(good morning) and saw my cake. I offered a bite, and then thought and gave them the whole piece. Duh, idiot. I don’t need the cake, I didn’t even want it, I took it out of respect for the people who gave it to me. Cake doesn’t mean the same thing to me.

A little later that day, Richard and I wanted to get a few things from the market. It is about an eight minute walk from here, through the asfalto. Everyone was out on the street in front of their houses, drinking and talking, chairs brought outside, music is playing, it is the celebration of the resurrection and hope, and everyone here participates. Young, old, rich, and poor.

I’m not as frightened walking through this part of town as I am in the favela. I’m actually pretty comfortable. Especially when, on our walk, one of my kids from the project sees me - he’s playing bola in the street, with a popped bola, and calls to me “Julia! Jule!” I turn to look, oh my gosh, my name being called out in the street by the children, what a wonderful thing that was! He brings me the bola, torn in half, it looks like a hat, and I tell him this, so then we make a game of wearing the hat. Nothing goes to waste here -- food, clothes, even broken toys are made into a new kind of toy if possible. We finish our game, and get to the market to find it shuttered. They closed on Good Friday. We had to go far away, into a more downtown area (Mario drove us) until we found an open market. It took us about 15 minutes. On the way, we saw three different pilgrimages from different churches, carrying the statue of the Virgin Mary. The first one choked me up, I don’t know why. Maybe because what I saw was so sincere. So real. It was a practice, not a rehearsal. I don’t know. Then we saw more. And by the big Rio Bridge you see in the pictures of the city, there was a huge passion play with a couple hundred people.

No colored eggs, no chocolate bunnies, no jelly beans. It is a holy day, not a holiday. I’m glad I got to look at it, like through a window, I felt like I was looking into the past, when the holiday was still connected to its original purpose. It was an odd, awesome experience.

Mario and Anita

Richard Geer, April 16

Marion. I'm not exactly sure when it was, but sometime in the last forty years, earlier rather than later, the worst thing in his career happened. It wasn't being arrested in Angola and jailed for several months. It wasn't even the deaths of the children who were corralled in the Institute by the police and shot to death. Those things were, perhaps, accepted as one accepts the weather. What nearly killed Mario was the cessation of the programs he'd spent decades building. If the Institute cannot serve, if Mario cannot serve, that is terrible. It was in a time of intense anti-American sentiment (happening again today), probably in the sixties. A director was brought on who was Brazilian, after a string of American directors, including Mario. This man was politically grounded and found that taking American money, help and food made the Institute appear to be in thrall to the Americans. So programs closed and people went hungry and jobless in the name of political correctness. At that moment in the Institute's history, little more than half way through the century, its trajectory faltered. The Institute today is a shadow of itself in its prime. One could say that Marion (locals call him "Mario") is the same, now he is an old man, then he was young and vital. But Marion is not done with service, nor is Anita, nor, I hope is the Institute.

Today it isn't the fascism of political correctness, it is the fascism of religious correctness in the guise of fundamental Methodism, and Marion hates it. The church wants souls, not mouths, converts, not friends. Throughout their careers, Marion and Anita have acted for hearts, mouths and minds, not for souls. The souls are left free to choose. This may be an error, but it is one I'm choosing to make as well. Ronaldo tells of being one of the boys playing courtyard soccer when it came time to stop, five o'clock. The boys begged Marion to let them continue playing, till eight, he told them. But in a few minutes he reappeared carrying four chairs. Without a word spoken, without a look from Marion, the boys stopped playing soccer and helped Marion move chairs and desks. "Every day for fifteen years this place helped me. But it also taught me, through example, always example, to help others."

We were talking about choir the other day, and Ronaldo, in his fifties, told Anita, "I'm poor today because of you." Anita was his choir teacher and she told him he had a good voice. Today he is a composer, singer, guitarist, writer and director. "It's her fault."

Ronaldo took us to see his daughter's production. She is co-director of a group whose Brazilian name means "Theater of Fear." We went to see their production called "The protest." It wasn't good, and neither Jules nor I had the heart to tell Ronaldo. We managed, rather gracefully I thought, to avoid judgment. The context of the show was theater ripped from the daily headlines of violence. What was wrong with the show was that it was drawn from a newspaper, not from a human breast. The specificity that would have been in a first person account was separated by two degrees, one journalistic, one theatrical. Of course Jules and I couldn't understand a word they said. But good theater is apparent, even if its words are foreign because its choices are particular. We saw generalities. Situations depicted without being observed. The effect was like a park instead of a rain forest. In the rain forest are many species in their synergy and diversity. Then there is the park with one grass and three or four kinds of tree. Monotonous.

The young actors were wonderful people, as we found out later over drinks. I enjoyed talking to them about stories and community. I thanked them for their show. Ronaldo's words came back to me: "My daughter, Gabrielle's, company (a middleclass theater company in Rio performing socially relevant plays) talks about 'the violence' in their performances, but they have no connection with any of it." It showed. Ronaldo went on "Our cast, the people in this play we are shaping, they live this violence first hand." Theirs is local expertise, and when it comes on stage it is invariably powerful and real.

Out of Place Princess

My room. Humble, but much more than any one I'm working with has. Life is so different here. Homesickness kicks in on days like this.

The Princess

Jules Corriere, April 17

It started raining last night, a thick, heavy tropical rain. Umbrellas are a laugh in the tropics. The only thing to do is let the rain just fall, and deal with it.

I live in the building across the compound from where we go to eat. I live on the third floor, accessible by stairs along the outside of the buildings, so it’s three flights up to go home, and three flights down, and a walk up the hill and then another couple of flights of outdoor stone steps to get to the eating area. At least the eating area is mostly covered, it has a roof, but the walls don’t meet the ceiling, so rain blows in a little. It was a damp breakfast and lunch. And dinner.

It is nice that it has cooled things off here. And getting soaked tends to cool a body off, too. I’ve just finished drying up for the second time today. I don’t change clothes between, because I don’t want to create more laundry. It’s been one big wet T-shirt contest. (I’m not winning, either!)

The rain cleaned the air, and I’m grateful. Yesterday, a man below my building was burning trash and tires for most of the day. I had to close my computer, the black smoke was coming in the windows and soot was getting everywhere. I wore a scarf around my nose and mouth for a little while, but it was so hot yesterday, close to 90, and it just got too hot. Not to mention I looked like the guys in O Trafico. Haha. But now, the air is cooler and softer. More breathable. And that man can’t burn tires in the rain. Nice.

Our stages were delivered this morning, in about 12,530 pieces. What a gift. Our friend, Christian Nacht, owns a company that puts up stages for different groups all over South America. He is the one who put in the stages and seating for the Rolling Stones concert here on the beaches of Rio just a few weeks ago. He’s a friend to some of us here, and he donated the use of his equipment for stages and seating for our production. What a gift.

He delivered it early, so our actors will have nearly a full month to rehearse on their spaces. Of course, I feel sorry for the poor guys here-- the trucks came in with 10 tons of equipment to unload in the pouring rain. No, for once I didn’t go down and try to help. I am still not 100% recovered from my surgery last month, and I’m not going to push it, especially when it looked like there were enough hands.

Inside the pavilion, we are experiencing the first heavy rainfall since the siege, and the floor is a mess. Some of the guys are taking turns using a giant squeegie to push the water out of the building. Puddles are all over the floor, a few inches deep in places, where the rain is falling through the bullet holes.

We have so much more leverage here to put up staging. We get to move it where we want, and we don’t have the usual hassles of the Fire Marshall (like the one in Swamp Gravy) telling us we can’t do this or we can’t do that. We told this to Steve, the son of the Institute’s director, who is helping us with stages and lighting, and he said, “No, you don’t have to worry about fire codes here. You just have to worry about 'under fire' codes.”

What to do in case of coming under fire? Egads! In that building? Pray, I guess, because that roof isn’t going to protect you from anything! Haha. It is Swiss cheese.

Trying to laugh. The truth is, I’m a princess. I’m not cut out for this work. I don’t have any business being here. I look at Mario and Anita, how they are here just about every single day, for forty years. They are saints. I couldn’t do something like that for such an extended period. I’m not that good a person. I’m feeling homesick, and guilty because I’m homesick while I’m trying to do this work. I’m just not that selfless a person. I’m sharing a bathroom with three other men. (I guess I should be glad I’m not sharing it with the whole building.) The class system is such that I can’t go into the kitchen across the way and fix something for myself. I like beans and rice, I do, and I am grateful to be fed. But part of who I am is doing things like that for myself. I like to cook. I like to serve. And God knows, I like variety. I’m not allowed any of that here. And I miss it.

I really want to cook dinner. It’s one of the things I do, that I like to do. At least maybe cook for myself and Richard and Ronaldo. Culturally, I’m not permitted to do that here. They have people to do that. And before some of you write back and tell me how inappropriate I am for going along with that kind of system, you have to know there are lots of people complicit with this behavior, including the people who do the serving. Julia became very angry with me the other day when I tried to help put things out on the table. She pushed me away from the dishes - I was trying to help. But that is her job, not just her place. Her livelihood depends on it, and when I start to do some of her work, she sees it as me possibly taking work away from her. We have to do better than that when we find ourselves in other cultures that we might not agree with, nor fully understand. Assumptions get us in trouble. You could assume, under a purely American philosophy, that Julia would want to be liberated from such servitude. But…What I view as servitude, they view as gainful, legal employment, without which, they would be in a much more difficult place. It is very complicated here. This was the last place to abolish slavery (as we in the colonies knew it) and this favela was founded by the people who were released under the birth act. People were still slaves, and after the act, anyone born to slaves were free, but their mothers and fathers were still owned. Consequently, through this act, slavery actually continued into the 20th century. This is a culture with a living memory of actual servitude, not just philosophical.

So. Not being able to do the things I like to do, simple things, makes me even more home sick. I know, boo-hoo, poor me. But I’m not trying to hide behind anything. I am a princess. You guys know me, and know that about me. I will do just about anything for anyone, I’m a giving person in that way, but I like to have my little princessy things, or I’m not a happy girl. And one of my little things is a long leash. The danger is such here, that I am on a very short leash, and not really able to go anywhere on my own. People have been promising me for a week now to take me out, either to the beach, or shopping, or to Corcovado, so I could get away - not by myself, but at least have a little variety to my life in the favela. Well, it ain’t happened yet. I could take a bus, like I did the other night to go to the theater production that I watched with Richard and Ronaldo. But the state department advises against using public transportation, because that is where travelers experience the most violence. (haha, except when travelers come to the favelas for some damn fool reason!)

There isn’t anywhere to go when it rains like this, and the rain here is heavy and lasts for days. Soon we will be deep into the rehearsal process and there will be no time to get away. So, I’m here. Working. Just working. And sitting. And you will get this email several days from now, because when it rains here, the internet is not available, either. Waaaa. But I never denied being a princess.

SHULA ULTRA VESA (It is Raining Another Day)

Juless Corriere, April 18

Internet is still down, so you won't know about the rain until it is over.

The stages are almost fully in place now. The design is dynamic. And, thank heavens, I've completed writing Act II. I won't have my usual edit time to polish this baby, but Ronaldo, my composer, translator and co-director, will help with this, I'm sure. As he translates from my English into Portuguese, he'll be able to keep the poetic edge I'll need, and clean up language as he translates.

We're having some slowness in getting adults in the performance. And getting them into rehearsal. They came to the first few rehearsals, none of the roles were assigned yet. But Ronaldo just left to meet with a group to recruit some folks. And we've got some people from the Institute who said they want to be in it.

Solitaire on the Titanic

Richard Geer, April 19

We hit the wall today. Jules started to bang it and bleed yesterday. I felt it today. It is the impossibility of doing what we are used to doing easily. For instance, at this moment there is no Internet in this entire facility. It rained yesterday and the Internet on our side of the commons spluttered out. It wasn't in our dining room as had been promised. The bright blue high-speed cable, like the snake in the garden, mocked us. Even downstairs in the office, off the back of one of the main computers, the cable was useless. "When it rains, the Internet is sometimes off." Across the commons, the other Mario helped me to connect. That was two days ago and it took more than an hour of hexidecimal codes and little windows notification boxes in English for a Portuguese speaker to guess at. I was doubly useless--Portuguese and Computerese, no hablo.

Mario knew a lot, but he was over the wall in Brazil, my computer was all US.

And today when we needed it, the computer room was locked anyway. So we tried burning CDs. CDs are rare as gold, only a very few in the whole place. Both Jules and I can burn to CDs--record files on CDs, Jules can even burn a DVD. But the computers here are so old that not one in the whole place can burn a CD, let alone a DVD. So we can give files to the ICP, but not the other way round. Their computers still use floppy disks, banished from our laptops two generations ago. We couldn't send a file through the Internet and we couldn't burn, so we couldn't get back a translated copy of the text.

Well, now we do, and this is how it happened. Downstairs in the back of one of the old desktop computers Ronaldo found a little USB port. Oh, blessed aperture. We have this little 512 MB memory stick that Jules' fabulous husband bought her. So Ronaldo shoved his little antique floppy up front and the little USB in the rear and the bytes started dancing the light fantastic. Fertilization, gestation. No parturition. Next chapter. Not a printer at the institute worked. I stared down their old warhorses, but ended up blinking first. The word processor said "print," the printer said, "aye, sir!" but not a damn thing dropped out. But who cares about us, we're only sort of directors and writers. Anyway, we had the files, but the cast doesn't have scripts.

Meanwhile upstairs a rowdy marble-throwing menagerie of mostly children is accomplishing damn all. Another evening lining up as a total write off. I decided to drop out and type up some publicity related stuff that had to be done tonight. Got it licked, got it burned on our last or second to last CD and handed it off to Anita to take home and shove up on the Internet. I came upstairs and Ronaldo is sitting with about fifteen people from ages 8 to 28 and over at the side Jules is all by herself typing away. But I see the green screen from feet away and can't believe my eyes. She's in rehearsal playing computer solitaire. My tickle box got tipped over and I lost it. Playing solitaire while the Titanic, hell with the Titanic, somebody's cheesy yacht, is taking on water like a bitch.

And that was about the end of the horrible terrible really bad stuff. I actually got two actors and went off to our suite, away from the noise, and did a bit of work. Acting work. It was very nice, even through Adenaldo as the interpreter. Lielson was my actor, he'll be a good Young Doctor Tucker, the founder of the ICP.

INDIAN DAY - Jules Corriere, April 19

Today is "Indian Day". It is a national holiday to celebrate the native Indians in the country. All of the children here are dressed in Indian costumes. There is such poverty, but the school has found a way to get all of the children a sort of costume, made from muslin, burlap, old sheets, etc., and the children are all wearing them today. Indians dressed as Indians. It's quite a wonderful sight. The costumes they made are colorful and beautiful. It sort of reminds me of what we do for our kids in Kindergarten for the Thanksgiving holiday. But here, the traditional Indian songs are still in the local vocabulary and memory. The children are outside of my window singing those songs right now.

The pigs have come down the hill today. The sow just had babies, and a little piggy was next to her this morning. Richard and I got some photos of three of them, including the big porco. He would make a feast, he's huge, but everyone here knows not to harm any of them. They belong to the leader of the Commando Verhmelho. They are his pets. If you eat his porco, he will eat you, haha.

Jules Meets Claude, the Great Pig - (Jules Calls hime Claude, we're not sure what his Brazilian name is...)

The pigs (um porcos) dine on the garbage on the hill. We sit at the bottom of the favela. There is a very steep hill leading up to the first line of buildings, and the hill between us has always been a sort of dumping ground. It is not as bad as it once was, because now the municipal garbage collectors are allowed into the bottom street of the favela. The other streets leading up are far too narrow for cars. For one hundred years, these narrow roads were dirt and mud, but last year, they put down concrete. It's much safer now. Fewer houses have fallen down the hill due to heavy rains. And it makes things more sanitary, as well.

The script took on an edgier turn than I expected. It is still very safe for the favela people, but there are some things about the church here, well, it just kind of slipped in. I don't know if it will be allowed to stay in, but there are things that I thought were important to be said, because a few people had the courage to speak them. The biggest idea is that of the judgment, almost persecution, that many feel from the church (not the Institute, but the church associated with it.) To give an example, there are two capoiera groups (traditional African-influenced dance/music/self defense) who will be participating in our event. When the pastor here found out, he was very upset. "We can't have that. And if we do, people will leave. If you put those groups on our poster, we won't participate, we will not be with them for any reason." He wants to work only with good Christians. He doesn't want anyone else coming here to the church or to the Institute. He wants to keep his flock pure.

What you need to know about this church was that less than one hundred years ago, when this church and Institute were founded by Dr. Tucker, it was during a time when the Catholics here had a stronghold on the government, and the laws were those of the Catholic Church. Dr. Tucker, a Methodist with the Protestant movement, was the hunted. A lynch mob came after him, they burned Bibles, he and others with him were persecuted. He escaped, and continued his work here. He created service programs, which ended up serving some of the very people who had persecuted him.

A long-time Institute director, Marion Way, is very disturbed by this new-century behavior of the evangelists, like that of the new pastor. He says they are more interested in winning souls (driving up membership) than doing the work of God, which to him, is service. He is afraid that the Church, which is related to the Institute, is becoming the very monster it was fighting only one hundred years ago. Exclusion and judgment seem to be in practice in a high degree. So, some of that has come out in the play. But I spoke about it in historical terms, rather than doing "confrontational theater." We don't need to be pissing off anybody here. But looking at it through an historical perspective, it can be an opportunity for self-examination.

The question is: Are you serving your church by being here - trying to win membership and support, or are you serving the people by being here? It is a complicated question. The answer, as I observe it, is yes to both. We'll see if what I have done with it will fly or be censored. We'll see.

Oh, man. The police just showed up. We'll also see what that's about, too. It's just one car, and it's the city police, not the military, so that's at least good. Three heavily armed police are up the hill, I have a clear view of them from my window. I asked Richard to take a picture for me. I'll send it when I can. There wasn't any fighting. They just went up to conduct business. (Probably taking bribes to assure a week of peace.)

(I'll send picture once I'm back in the states. It's a great, scary shot.)

WE DRANK A LOT OF WINE - Jules Corriere, April 20

Oh, my God, I am sitting here with this fabulous Brazilian director named Billy, but he speaks no English, I speak no Portuguese, the printers at the Institute are all broken, I have rehearsal schedules that cannot be published, I have written a text that cannot be read by anyone. We've had some rehearsals, mostly with kids, but now the adults are showing up, we really need them, and it is utterly disorganized. I guess it is a cultural thing to have so many things break down like this, but it is slowly driving me crazy. I'm having a hard time dealing with it because I'm usually the stage manager that whips people into on-time schedules, but nothing in Brazil is on time. I should have known that when my plane trip was four hours late coming into Rio! And no one really had anything to say about it. That's just life here~! I should laugh. I actually am laughing right now, but I wasn't earlier this afternoon, I was getting frustrated about not getting the work done and having it ready, I'm feeling ineffective, but I guess I just need to go, oh, well, it's just going to be this way. It got so crazy tonight, I did finally give up. Richard left, (he was in the nice air-conditioned and quiet room downstairs, working on a paragraph about our work for a man associated with Viva Rio.) I was left upstairs, alone, with about 20 kids and some adults, and Billy, He was nowhere, Ronaldo (who is also my translator) was nowhere, I don't know what to do or how to get started, so I just turned on my computer and started playing solitaire. It was mass chaos. The kids are playing this game with marbles, tossing them across the room to hit a wall and see how far it will roll back, and I'm just sure that one of them will hit and smash my computer. I don't know how to tell them to stop. SO I gave in to the chaos. Richard came down, relaxed, cool, happy, (he'd been out of the loop of chaos for more than an hour.) He looked at me and said "Oh, my god. You have lost it." He knew it, too. When I turn myself off and start playing video games during the middle of what was supposed to be a rehearsal, he knew I was at the complete and total edge of my sanity. We drank a lot of wine.

NOT LOST IN TRANSLATION - Jules Corriere, April 21

Finally, finally, finally. Things are pulling together. We’ve got actors coming regularly, and I think I have gotten my musician/composer/director/translator to come to rehearsal on time (meaning, no more than 15 minutes late!)

Richard took one group tonight, along with a translator. Ronaldo and I were to take another group. Ronaldo is very Brazilian. He’s a very Brazilian director. It gets loud and chaotic. I looked around and realized some of the chaos came from a group of five teenage girls who were here, but hadn’t been assigned roles yet. I found a scene in which they could all be together, and I took them with me, scripts (translated in Portuguese) in hand. And we went to another room. It was gloriously quieter. Only the noise of the soccer game outside the window in the courtyard, and the bus traffic, but not screaming kids. Ahhh. It was great.

Since I wrote the script, I know what it is, what they are saying, even when speaking Portuguese. With body language, I direct them in how to portray the roles - some sassy, some gruff, some “know-it-all”.

Amadeus laughed at me tonight when I finished - he is one of my room mates, and has decided to join the cast. He said I did OK, but I need to be fluent in Portuguese starting tomorrow!

Oh, gosh. I had a fun day.

Then, at dinner, my German friends were there, Simon and Martin. Martin has decided to join the cast. We spoke German and English at the table, he would switch over into Portuguese as well, but I’m starting to pick up on the language, so every fifth word or so I’m understanding. It’s much better than when I first got here.

The best time today was when I met a new Pastor. His name is Eduandro Machado, and he works with the Prison Ministry, as well as with an International Watch group, like those who look into places liike Guantanamo Bay, etc.) He is an absolutely lovely man, with the most beautiful energy. I really admire the work he does, it is very much like the work of Bill Cleveland. Some of you know who that is, he’s one of my personal gods in this kind of work. With Eduandro, I realized how intimate language really is. When you have good energy, when you come from your heart, THAT translates.

If, If, If... - Jules Corriere, April 22

A day of boredom with pockets of violence.

We have rehearsals in the evening, but that leaves all of the morning and afternoons vacant - to do what? Here? stare at walls, or hide behind them, your choice.

The internet was down again yesterday. That broke me a little bit. I had such hope when I was connected to the outside world, and then poof, it was gone.

Richard went for a walk with me late yesterday afternoon, around 4:00. We got around the corner on our way to cemetery, and the building on the corner is falling down, with plywood nailed up where some bricks used to be. This is an asfalto house, like I mentioned in an earlier journal. It is hot, so one board that serves as a kind of door is down. Lots of people have taken the boards down for the afternoon, since it is so hot. (the smell again...) These houses are open for everyone to see. All of the houses around here are this way, so there is nothing strange about it to them. Inside, as Richard and I pass (and remember, the difference between "inside and "outside" is a stone step that serves as a threshold, but there are no walls) A man "inside" grabs a woman by her hair and slams her into the ground. She got up and ran past him, "outside", then past us, and the guy just looked at me, I turned my eyes away and walked quickly around a pole that was at the corner, Richard walked past too, neither one of us knowing what to do. i just wanted to get the hell out of there before something else happened. She ran away down the road, which I was glad to see. But, she lives there, she'll be back, if she isn't already. Violence is ordinary and life is cheap here.

Then we went back to the Institute.

We had rehearsals in the evening, they were going pretty well. I did more of the "body language" directing, along with the little of the language I am picking up (learning phrases like "come with me" "speak louder"). It is going surprisingly well, and the folks here seem to like the script. And the stages are wonderful. The Pavilion echoes. We'll have to figure out a way that the echoes don't take away from the show. But the rehearsals that we have been having have been pretty good. We still need about 5 more good adults.

Hugo. He's about 11 years old, no - 12 now, he had a birthday two days ago. I brought some happy meal toys with me here to Brazil, and among them was a digital watch. I put it in an old box, with a piece of candy and told him Feliz aniversario. He put it on right away, had me help him put it on. He was thrilled, then he hid the candy, and went outside to eat it, but before he did, he called his friend, the other boy in the cast his age, and he shared it with his amigo.

Hugo comes to all the rehearsals. He wants to work, he wants to help, he wants to learn, but also to teach - I turned on my computer, and he showed me some things about my games. Hugo is the age of the boys recruited by the drug cartels. Please, god, I think each day I see him, please, let Hugo say no. Boys can say no, there are not a lot of threats or anything like that, there are plenty of people ready to get the quick easy money promised by the CV. But once you make that commitment, that is it. You know things others shouldn't and the only way out is a bullet. Most of the time, the bullets come before they turn 17. The largest percentage of killings happen with the little favelitos who guard the entrance. They are given Kalishnikov rifles and shoot anyone coming in who isn't supposed to - other drug gangs, or police. Often, they are fired back on. They are the most expendable. Please...not my Hugo. We are finding a place for him to do more. Some kind of internship. Something. If this could be a long-lasting project … if, if, if, … he could become a member of the company. If, if if. But it is so difficult to say if it could happen. I love this kid. Big heart, big brains, big potential. If.

Richard, Ronaldo and I came back and watched a movie together. Then went off to sleep.

A few hours later, the war started again. It is so strange - the contrast of this place. Most of the days are long, long, drawn out and boring, and then, it becomes explosive.

I am having different reactions to the gun fire these days. Last night, it was strange, I heard the big guns first, the police tried to go into the favela with an armored car. But just one car. Makes me wonder what they were trying to accomplish. I heard some pops from a small gun, like a .45, pop, pop, pop, then some big ones "boom boom boom". from the police car. Then the kalishnikov. The kalishnikovs have a very distinct pattern sound to them. And they are the easiest to follow by listening, so you can know where it is coming from, and whether or not you should look for a more substantial shelter. One of the things I've been educated on here.

Poor Ronaldo. He really has terrible timing when things start to heat up. Last time he was outside of the gates, and couldn't get the lock open. Last night, he was in the toilet. He said "So, I put my head down, I stay there, mostly, I protect my pen". We all laughed.

With the first few shots, I'm having a similar reaction as before, I startle, but I don't pop my head up anymore to see where it's coming from - that was my first instinct when I got here, try to see where the shots are coming from. but that's not the safest thing to do. My body jerks now at the sound, but now, instead of coming from a fear reaction (I used to get kind of shaky/scared) I get this adrenaline rush - I can feel it, it's really weird, this kind of scientific reaction - I start, then, hold still, I listen first to see if I can here from which direction it is coming. Then I listen for gun fire coming from another direction. If that happens, I know to stay down. If it's just one gun, or a gun in one direction, it's not as big a problem. Sometimes, people just fire guns. If there are two different guns, or the sounds of the shots are coming from different directions, I know it's a fight, and best to lay low. Don't even get up to close a window. i thought about it last night, my windows are always open for the air, but my bed is against the wall, and not under the window, so it's safe. This is a really thick walled building.

Last night I heard specifically three different kinds of guns. There may have been more, but the fight only lasted about 35 minutes. Then the police ran away. As I said, I don't know what they thought they would accomplish. Only the military can go up there successfully. The *** are just better armed than the city police. I guess the police figured since it was late (about 2:00 in the morning) that they might catch them unawares, but as I said before, there are people stationed at the bottom of the hill all the time.

It wasn't a bad one this time. The fights that last only an hour or less, we call those fireworks. I think I fell asleep before it was finished, because I heard the sound of the kalishnikovs moving further away, and knew it would be ok. I don't know when Ronaldo made it back to bed. He wasn't leaving until he knew his pen was safe.

A HUNDRED YEARS SPEAK - Richard Geer, April 22

Jules has been so much more faithful with her journaling. Part of it is distraction, she's very homesick and feels cloistered here. The walls are very thick in this old building. I love the architecture of large open windows doubly shuttered with immovable louvres on the main frame of the shutter with some glass above them, but the shutters themselves are open. Hinged to this shutter is a smaller solid door that fastens with a slide bolt to the shutter so it can swing as one. One can have wide-open windows, half glass half louvre, or solid wood. The walls on this top floor, the third, are easily a foot thick. On the lowest floor they are more like three feet thick.

Still the noise is RIGHT HERE with you all the time. The foot of the Morro da Provedencia rests just below my window, and around its perimeter is a heavily traveled road down which buses, incredibly, horrifyingly fast buses rifle along at any hour. Then there is the ever-present laughing and shouting of children.

Last night Jules and Ronaldo awakened to about half an hour of intermittent gunfire from the favela. Jules listened before drifting off to sleep as the fusillades seemed to be moving away. She is pleased that she is calm enough to fall asleep in gunfire. Ronaldo was caught in the bathroom and was worried enough to remain there for most of it. With my earplugs I heard none of it. From up the hill on many nights comes the sound of parties in the open-air community hall, which is nothing more than a sheet metal roof over an area the size of a basketball court. The sound from this and other sources assails the ear. You don't decide to listen or not, as you might to the city sounds at home. It is HERE. Roaring. Noise pollution will be a major concern for all the parts of the performance.

We had rehearsal today outdoors in the sunlight, instead of evening. We'll begin the play that way because we walk through the graveyard. At eleven in the morning Ronaldo began working with the Eliete scene as Jules and I continued to do script related work in the room. We could see them at about our eye level across the quad, on the hillside where the new steps climb the cemetery wall.

I've included a picture of that in this email. Ronaldo is playing as the cast of Eliete is singing. On the steps the man seated is Lielsen, one of the Young Dr. Tuckers. In the rear, in a pink shirt, is the real Eliete, watching rehearsal.

We worked also with the Capoeira group. I don't know if that's spelled right. Capoeira is a form of martial arts developed by Brazilian slaves to resist their bondage. It is symbolic of resistance. It is also associated, though incorrectly, with the religion of Macumba. So the evangelical Methodists (NOT Marion and Anita) are suspicious and fearful of Capoeira. The Methodist pastor insisted we not put their name on the poster. Instead, Jules has written the argument about inclusion versus exclusion of Others into the script. The Capoeira group is more African, darker skinned than the average of people around here. They were chanting a call and response during their own rehearsal time in the Cannonball factory. It was basically a chant of racial pride from what Renaldo could tell me. The group is lead by a drummer and someone playing the typical instrument of Capoeira, a pice of bamboo bent like a bow, five feet long, with a gourd attached for resonance. The steel string is struck to produce a tone and vibrating rhythm. From the circle pairs of children dance forth to whirl and tumble in dance battles with one another. It is exciting and beautiful. We finished rehearsal by walking the route of Young Dr. Tucker with Lielsen, Jules and me. Cosme came too. The timing to the graveyard gate worked well. In the cemetery we came across a group of our girls, so we cast them on the spot in the scene. Several to talk together, and another, a wraith, to walk into the ground as Tucker speaks of the forgotten children lying in unmarked graves. Then we had lunch. A little progress!

The performance. With exactly three weeks to go, we are just beginning to see our way. We have a script, it is translated, we have music, we have some of the cast. We do not have all those things together at the same time--Oh, my, the perfect illustration of my point just happened; a knock at the door just now, there stands Edmundo for rehearsal; but there is no rehearsal, he apologizes, he forgot to call Marion and check the schedule.

A production begins as one idea. Then it divides and the pieces stumble apart. As we begin to rehearse the pieces propagate like randy bunnies. No longer one idea like "the cast," but scores of individual people, and hundreds of different moments at which people and tasks and particular places are must intersect and often don't. We are perhaps just past the widest point, but the mother of chaos lies ahead. That is the period of production when all the elbows on all those ideas and people have to accommodate one another like tall passengers economy class. Like flight for a bumble bee, it's impossible but not un-doable. It is no harder than a million things like conception, death or love. Finally, the production is one thing again, and a hundred years speak.

ONE LIFE - Jules Corriere, April 22

The One. I spoke about the one life that might be affected here. Well, one life is affected by my visit here. The only one that could be.

What difference, in the long run, in the greater scheme of things in life will it make? I don't know. One person will examine life differently. Probably live life differently. Just one life different. I guess it makes a difference.

I keep walking in the cemetery under the favela.

I come here to read the epitaphs. I read them for those who have died, so close to here, and have no epitaph. It is the most painful thing I can imagine, and I see it every day here -- people, children, lost to the world, and unknown, not a word spoken about their death, or what might have been possible.

Every life has value. Every life is a story, full of great sorrow, great joy, some boring days, and other days filled with so much excitement you wish you were two people to live them. Lives so full of possibility, not the possibility of greatness in the way of politics, but greatness of heart. The possibility to perform acts of great kindness and small gestures, a smile, a laugh, a touch, which seem to mean nothing, but like the flap of a butterfly's wing, is capable of creating great change to sweep across the world.

I come here to remember the little butterflies, who never had a chance to flap their wings. You will not find them here. Their voices do not speak to us across time. I cannot speak for them, but I can remember them.

CINDERELLA GOES FOR A DIET COKE - Jules Corriere, April 24

It's a beautiful day here today. Sun is out, but it's not too hot. We had a rehearsal with some kids in classes here. They, along with their teachers, will be in the show. These are some of the kids I wrote about on Indian Day. They were so cute, and I had a lot of fun with them. Anita translated for me, I explained to them what their scene was about, but I did so in a "once upon a time" way with them. They are in a scene about when the Institute decided to create a camp and went looking for their perfect little Eden for the children. I did more acting and animal noises than speaking. The story goes, in kids terms of course, that the people who were sent to look for the camp described the beautiful birds in the eucalyptus trees, the ducks swimming in the pond which they would turn into the swimming hole for the children, and the chickens in the chicken coops. The leaders would actually turn the chicken coops into the kids cabins! As I told it, and acted out the different animals (especially the chickens) they laughed, and I think they had as much fun as I did. I hope so.

It's been gloriously quiet today. Just the usual city traffic and nothing else. Ahhhhh. It's been two days without gunshots! Ahhhhhhh.

This princess has become a bit of a Cinderella. Richard was taking a nap in his room. Ronaldo in his. I couldn't sleep. I grabbed a rag that sort of serves as a shower mat (eww, disgusting. I know, but it's all I've got.) I brought it to the sink and poured some cleaner on it. I don't know what the stuff is, but it smells like cleaner. And then I carried it to my room and swabbed my floor with it. My feet have been getting filthy from just going to turn off the light before bed. Then, I rinsed the rag out, it was black, I added more cleaner, and got the hallway. That's when I looked up, and there he was. Richard had awakened, saw me out there, grabbed his camera. He knew he better get the shot while he could! He couldn't believe his eyes! Haha! Oh, i was a mess. But now my floor is not. It's so nice to walk on it. I figure I could do that about every three days or so. It really helps. I wipe my computer off daily, Richard and I both do, and the paper towels we use are black each day. That is why people keep everything covered here, to protect it from the pollution.

That idea of things being covered has become a visual motif in our play.

We've got about a hundred sheets that the hotel donated to us. We're using those in the play. (then we'll distribute them to the people, I suppose.) Here, what you find when you go to any meal, is a tray with cups, but a towel over them. A tray with silverware, but a towel over them. The food has towels over it, everything, everything is covered, even once the towels are cleaned, they have a towel over them, or are placed in a plastic bag and tied, to protect it from the pollution. So, Richard had the great idea of covering things in the play- memories, people, artifacts. And, in the parallel story I tell of the nine boys who were murdered here, we cover bodies, too. Pretty cool idea. We're also doing things with the sheets in the graveyard. We have to be careful, people here get freaky about graveyards. Way more than what I've experienced in the US. We now have a staircase built from the cemetery, over the walls into the Institute. They look at me and say "YOU did this!"

It was my wild hair notion last year to do a progressive theater piece - starting out at the Institute, walking outside of the gates, (the idea that we are now in this wild place, without a home, without the safety of gates or walls, just like Dr. Tucker experienced when he came here.) and then, with an actor as a guide, and a series of scenes performed strategically along the path, we go to the cemetery. Lots of people from the Institute are buried here, and so the voices from the past call out and are heard again. I just loved that notion when it struck me. And then I thought, it would be cool if we could create a way over the wall, and back into the Institute. We could somehow go over the wall, like the favelitos, only we could do it without sneaking, and we could create a way for THEM inside, too, without sneaking. An opportunity for inclusivity during this production.

And, well, we have a staircase erected now - the guys came in and built it with the stage equipment provided by Christian, whom I wrote about earlier. It looks great! And the favelitos are using it to come over the wall now, instead of the other way, which was a little more difficult. The wall will come down, after the show, but right now, there is a whole new dynamic about the place, about it's openness.

I walked with Richard and Ronaldo to the market. On our way, two federales (not in uniform, which is scary) were on the sidewalk, with big machine guns, and they were looking at people's documents. I quit speaking to Ronaldo. We just shut up and walked by. I had forgotten to put a copy of my passport in my pocket before I left, and I was afraid I'd be asked for it. You need to keep a copy of your passport with you all the time here. I stupidly forgot. But they were only looking for contraband from the guys on the sidewalk and in their building. I leaned over toward Richard after we walked past them and whispered "Let's put some pep in our step" Richard said "Oh, yeah" and we hot footed it to the market. On the way there, I wondered, is that diet coke I wanted worth all of this? I was surprised, when my answer was "yes." You have to allow yourself to get past the fear and have some of the little things you like, or life becomes a prison. It felt like prison last week, I am trying to create a different reality for the rest of the time I'm here--It worked, they were gone when we walked back.

… and then we had a CRAZED, but interesting rehearsal. Last week, I wrote to you about reaching the point where I lost it. At one point tonight, I looked at Richard, and I could tell, oh, yeah. He's losing it. It was his first big rehearsal with lots of people, the chaos, the noise, the translation problems. At one point I went and put my finger in his ear, to keep his brain from spilling out.

OK, so I didn't do that, but I looked at him, and the picture came to me to do it, and thinking it up is almost as good as really doing it!

LITTLE ANGELS - Jules Corriere, April 25

Feeling very tired, depressed.

I am having a hard time living here and trying to find some centered-ness within this violent, hard world.

I was in Richard's room crying this evening. There is so much going on here, I barely know where to start each day. And when I'm done with the day, what have I really accomplished? I just wanted a sign, just some little sign that it mattered. I miss my kids at home, I am on edge waiting for the next series of boom boom rattattatats. I don't understand anything - I'm not just talking language here, I'm talking about the culture of violence that has been allowed to spread so deeply, and so broadly. It is an accepted thing for these wonderful people I am working with to live in the world's most dangerous city outside of Baghdad (according to the Associated Press and the BBC.) How did it get this way? Why was it allowed? How could any reversal be possible? The people I am working with were born in the favala, and accept they will die in the favela, just as their parents, and their parents did. Where do they find their sense of centered-ness and peace and acceptance? My own heart aches to be here, to see everything I am seeing and to be part of it. I was at the point of giving up. My heart just can't take it, I feel like there's nothing here I'll be able to do, and that the whole situation is hopeless.

Then I started thinking I was going out of my mind. I thought I heard someone calling me outside. Man, I really am homesick. I went on talking to Richard, and I heard it again. A Brazilian mental hospital is NOT a place I want to visit. Then I hear singing, and my name being called again, and Richard hears it, too. We both get up and go to the window. Outside, Cosme and Hugo are serenading me. There they are, standing under my window, singing. When they are finished, Cosme yells up in very good English (he must have asked for lessons on how to say this, because he doesn't speak English) but he yells up to me "I love You, Jules! We love you!"

If you don't think I cried…

It was my sign, I guess. Love. I needed it. They saved my heart and my hope. I was feeling like everything was hopeless, and right then, these little angels gave it back to me.

I tell you, I could use a regular dose of it here. There is so little to remind me of hope. This is one of those moments I don't think I will ever forget. It's a great thing, to ask for a sign, and then, to get one. (And to have a few witnesses, so I know I didn't just imagine it all.)

IN THE NEWS WITH THE FEDERALIES AGAIN - Jules Corriere, April 26

With checkpoints on Rio de Janeiro's highways and a stormtrooper presence in nine favelas, Brazil's army pressed its search for eleven guns stolen from a local army depot, the Associated Press reports.

But, as the article notes, this "massive sweep to recover a handful of weapons" is, to put it mildly, "unusual" and, despite the presence of 1,500 troops, the army has yet to find any of the stolen guns.

That the traficantes have serious weaponry--often stolen from the armed forces--is nothing new. It has been known for years. The question is, why all the fuss now, particularly over ten assault rifles and a 9mm pistol?

Why isn't the army looking inside itself? The thieves were dressed in army regulation camouflage uniforms. How did they get them? And they apparently moved in and out of the arms depot with ease. How did that happen?

Given that the military is looking in favelas controlled by the C*** V*** including Morro do *** and Mangueira, this would lend credence to rumors that the authorities actually favor a rival drug gang called Amigos dos Amigos.

So far, one teenager has been gunned down, caught in the crossfire between the army and the drug dealers at Morro do ****, not far from Rio's famed central railway station.

Eight Killed in Rio Favela Fight

April 26, from the BBC, about the situation erupting here.

The Brazilian army occupied Rio slums two weeks ago. Eight people have been killed in Brazil during a gunfight between suspected drugs traffickers and policemen in a Rio de Janeiro shanty town.

The shooting started during a fight between rival gangs for control of the northern Imbarie slum, officials said.

It occurred after the Brazilian army ended a massive deployment in the city.

Rio de Janeiro - one of the world's most violent cities - has seen frequent clashes between security forces and members of heavily armed drug gangs.

FROM ASSOCIATED PFRESS

The army occupied slums in Rio two weeks ago in an operation that lasted nine days and involved 1,500 troops equipped with helicopters and armoured vehicles.

The move was aimed at recovering weapons stolen from a military base. It led to daily shootouts with drug gangs and left several people injured.

Human rights groups have criticised military tactics used in Rio de Janeiro.

They say security forces should switch tactics towards community policing to try to reduce the high levels of violence in the city